The rise and fall of the Kathmandu Valley’s cycling culture- Prashanta Khanal

Sourced from: The Record Nepal

In the last century, cycles have gone from a symbol of wealth and power to one of poverty, but that is slowly changing.

In the early decades of the 20th century, bicycles were out of reach for most commoners. Bicycles then symbolized wealth and prestige, and only the Ranas could afford them in Nepal.

Tirtha Narayan Manandhar, in his book Kathmandu: Then and Now, recounts how the first bicycles were imported to Kathmandu from Britain via India: “When my father was young, around the year 1903, some Ranas and certain dignitaries imported a few bicycles from India and they rode them for leisure. General Soor Samsher was one among them.”

Almost around the same time, cars too arrived in Kathmandu. Until 1953, as no motorable road connected the Tarai to the Kathmandu Valley, cars had to be carried on the backs of men from Bhimphedi to Kathmandu crossing the Chandragiri hills.

“In those days, my father and his generation used to call them sala-mwaa baggi [a buggy that doesn’t need horses to draw or pull],” writes Manandhar in his book.

Cars too were reserved for a few super-elites: the royals and the Rana rulers. The bicycles then were for rich elites.

In 1925, Manandhar’s father, Asta Narayan Manandhar, opened Kathmandu’s first bicycle store, named Pancha Narayan Asta Narayan in Kamalacchi, importing six British-made Hercules bicycles from Calcutta. Each bicycle cost around Rs 100 then, more than the annual salary of an ordinary government official. Later around 1934, the shop started importing Raleigh bicycles. And because they were able to reduce the transportation cost by packing as many as 25 disassembled bicycles in two large boxes, the Raleigh bicycle cost Rs 90.

The bicycles were transported by train from Calcutta to Amlekhjgunj via Raxaul, by lorry to Bhimphedi, and then by ropeway to Kathmandu. Before the construction of the ropeway in 1922, porters carried the bicycles from Bhimphedi to Kathmandu.

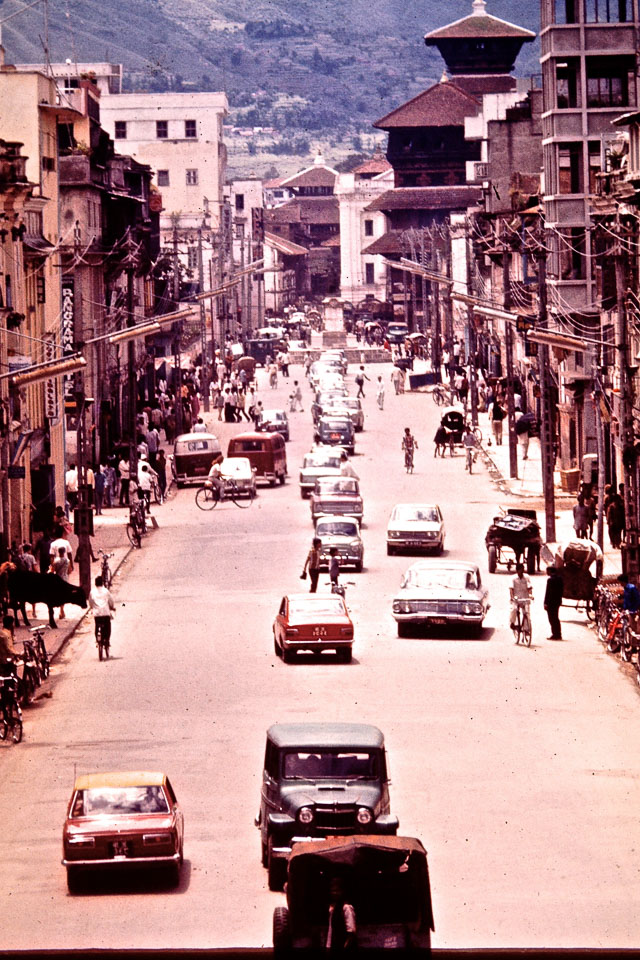

Bicycles in the 60s: from an elite toy to a commoner’s means of transport

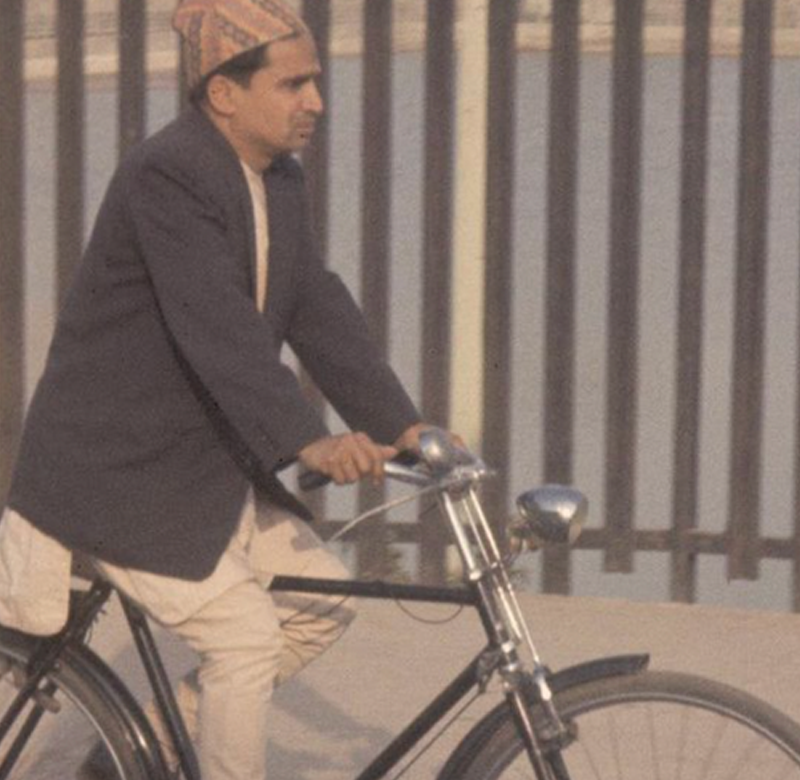

After joining a government office in 1962, engineer Bharat Sharma bought his first bicycle, a Hercules, for Rs 1,000, which was equivalent to three months of his salary. He commuted daily on his bicycle to his office and cycled religiously until the 2000s when he had to give it up because of his health.

Like Sharma, Padam Bahadur Shrestha, who worked as a musician with Radio Nepal in the 1950s, used to cycle to work every day — fifteen kilometers one way from Bhaktapur to Singhadurbar. In the 1970s, Radhakrishna Joshi, who taught at Tribhuvan University in Kirtipur too used a bicycle to commute to work from Dillibazar.

In the span of a few decades, bicycles had become the common man’s ride and a big part of Kathmandu’s streets. This was possible because, in the 1950s, factories started mass producing bicycles across India. Mass production meant prices came down and more people could afford them. By the 1960s, Indian bicycles adorned many homes of Kathmandu’s middle and lower-middle class.

“In the 1980s, our shop alone used to order 250 to 300 India’s Hero bicycles a month,” said Prachanda Manandhar, who used to run the Pancha Narayan Asta Narayan shop, established by his grandfather.

Besides several privately owned cycle shops in Kathmandu, the government-owned company Nepal Trading Limited too used to sell China-made bicycles. Several cycle rental shops and repair centers catered to the cycling demand. In the 1960s, cycle races were also organized in Tundikhel during the Ghodejatra (Pachahare) festival, along with horse races, which added to the bicycle’s popularity.

Campuses and government offices even built dedicated parking spaces for bicycles. In 1965, Gorkhapatra published a tender call from the government to build parking spaces for 400 bicycles and 100 to 120 motorcycles in Singhadurbar. In the mid-1970s, the Institute of Engineering too added a dedicated parking space for bicycles, which reflects the burgeoning cycling culture of the time. Unfortunately, that space has now been turned into parking for motorbikes.

For middle-class and working males, the bicycle soon became their symbol of pride. They would often take portrait photographs with their new bicycles.

Bicycles were still a luxury not everyone could afford in the mid-1970s. But Sumitra Manandhar Gurung and her siblings and cousins had grown up around them. Her family owned a bicycle store in Ason, Kathmandu. Here, her brothers and a cousin are out on a ride to Chobar.

Soon, the bicycle became a tool to resist political oppression. In 1975, Shree Krishna Nakarmi, a theatre artist and school principal, and his friend organized a cycle rally on Nhu Daya (the Newa New Year) with slogans written in Nepal Bhasa. They strategically planned the cycle rally to protest the suppression of their language and culture by the Panchayat regime, which had forced an “ek bhasha, ek bhesh, ek dharma, ek desh” (one language, one way of dress, one religion, one nation) nationalism onto all Nepalis.

“Each tol felicitated the rally participants and put tikas on them, which later turned into an annual practice of celebrating Nhu Daya,” recalled Prachanda Manandhar, who supported the rally by lending bicycles to participants from his shop. “The annual Nhu Daya cycle rally continued for a few more years and was later replaced by a motorbike rally.”

By the time Kathmandu stepped into the mid-70s, farmers from the city’s outskirts too started adopting bicycles to transport vegetables to the city’s markets. Earlier, Bhaktapur and Thimi farmers would walk all the way to Asan or Kalimati, carrying their produce in a kharpan (a carrying pole made out of bamboo). Bicycles eased their travel and saved time. Small vegetable retailers in the city too used bicycles to fetch vegetables from the wholesale Kalimati vegetable market.

However, the ratio of cycle users to the population was relatively low, compared to European cities with strong cycling cultures. Until the 1980s, the Valley’s settlements were densely confined within the historical urban areas of the three primary cities: Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur. People could easily walk from one end of the city to another. Social and marital relationships between the three cities were rare. This confined spatial and social environment limited the need for longer trips between the cities and thus the necessity of a bicycle. Also, because many people didn’t have office jobs, they neither required bicycles nor could they afford them.

The decline of cycling culture: From common transport to a poor man’s vehicle

Until the 1990s, the cycle was still the common man’s preferred mode of transport in the Valley. But after the 1990s that changed. And today, cycling culture has declined significantly. Once associated with social status, cycling has now been reduced to a vehicle for a poor person’s mobility. How did this shift happen? What were the turning points? What were social, economic, and political factors for the decline in cycling culture?

The easy answer to these questions is that cycling culture declined with the rise of motorbikes and cars.

The middle-class’s attraction towards cars and motorbikes started as early as the 1970s. In fact, even by the mid-60s, pictorial advertisements for cars and motorbikes had already started appearing in newspapers. And they continue to this day. A 1969 full-page car advert published in The Rising Nepal promoted a car as “a sense of style and prestige.”

Various foreign development projects in the country planted dreams of owning a car and motorbike among middle-class Nepalis, which earlier existed only among the elites, high-level government officials, and rich businessmen. It was around this time, in the 1960s, that many foreign investments and development assistance projects entered Nepal. These projects, especially hydropower projects, started providing their staff, both foreign and local, with cars and motorbikes for their daily commutes and field visits. Oftentimes, ministers and politicians misused the cars funded by the project for their own personal commute, which was infamously called ‘Pajero culture’. Gradually, the government too adopted the practice of giving a car or a motorbike to its employees.

“USAID insisted that its government advisors ride in jeeps driven by Nepali USAID employees,” said Doug Hall, who joined a USAID project in 1971 as a science advisor to the Ministry of Education. In 1968-69, Hall used to cycle daily from Handigaon, and later from Patan, to Durbar High School in Jamal, where he taught as a Peace Corps volunteer.

“After joining the project, I bought a motorbike for work and only occasionally rode my bicycle for a short trip to the bazaar,” he recalled.

After the mid-70s and 80s, many rich and upper-middle-class Nepalis purchased private vehicles, largely motorbikes, as they were far cheaper than cars. Motorbikes became a trend.

“When I joined campus in the late 1970s, students had already started romanticizing motorbikes,” said journalist and editor Kanak Mani Dixit.

Slowly after the 80s, cars and motorbikes, not bicycles, began to symbolize social prestige. People started to see bicycles as playthings for children. Among teenagers, new Chinese bicycles with straight handlebars were trendy and the Indian design, with a curved handlebar colloquially referred to as ‘budo cycle’, was considered unfashionable. The charm of a bicycle among adults gradually faded. Mass media too portrayed riding a car or a motorbike as something desirable for anyone seeking higher social status. Society began to view a bicycle as a poor man’s vehicle.

Bharat Sharma, the engineer, shares an incident he experienced in the 1990s:

“One day while cycling, a man from my neighborhood stopped me and asked me if I was an overseer. Immediately after a breath, he asked if I was an engineer. When I told him that I was an engineer, he brooded for a while and apologetically said that he could not imagine an engineer riding a bicycle.”

In a society where owning cars or motorbikes prevailed as part of social prestige, an engineer cycling, instead of driving a car or motorbike, appeared out of the ordinary.

Sharma was an exception, as most who could afford it shifted to private motor vehicles. As bicycles were associated with postmen, peons, and security guards, the rich and middle-class gave up cycling to maintain their social distance from the working class.

Rapid motorization after 1990: Beyond personal preference

After 1990, with the re-establishment of democracy, motorization in the country grew rapidly. Consequently, cycling culture and its status too declined.

In 1990, only 28,462 private motor vehicles (cars and motorbikes) were registered in the Kathmandu Valley, which is about 50 vehicles per 1,000 inhabitants (assuming private vehicles registered in Bagmati zone mostly ran in the Kathmandu Valley). But in 2011, this number had reached about 350 vehicles per 1,000 inhabitants, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics.

While the Valley’s population grew at the rate of about 4.3 percent, motor vehicles grew at the rate of 12-13 percent annually. The share of private vehicles increased significantly from 13.1 percent in 1991 to 30.2 percent in 2011, whereas cycling declined from 6.6 percent to 1.5 percent.

As a result, roads and streets started to clog with traffic. The city’s roads turned unsafe, especially for walking and cycling, becoming more and more perilous every year.

“The city’s narrow streets that once were not only for people to walk and cycle but also for the gods to go around in a chariot were gradually overtaken by motor vehicles,” said Sharma.

After 1990, the democratic governments wholeheartedly embraced modernist development agendas. Big infrastructure and ‘chillo sadak, chillo gadi’ (smooth roads, smooth cars) symbolized modernity, prosperity, and development. Wide roads and motor vehicles that people were deprived of during the Rana and Panchayat regimes became symbols of progress for the masses. For politicians and planners, cycling meant regression. For corrupt politicians and planners, large road infrastructure projects also meant opportunities for commission. Low-cost incremental changes such as walking and cycling carried no clout.

“As economic and political elites couldn’t understand the benefits of cycling, bicycles became passe,” said Dixit.

After the end of the Maoist conflict in 2006 and the end of the monarchy, the political rhetoric of ‘sambriddhi ra bikas’ (prosperity and progress) dominated the national discourse, which only exacerbated the same modernist development visions of megacities, wide roads, flyovers, cars, and metros.

Cycling had failed to enter the realm of political ambition.

Then, in 2011, then prime minister Baburam Bhattarai started a road widening campaign to woo Kathmandu’s rich, bourgeois class — the ones who were stuck in traffic jams. Road expansion further fueled the growth of private vehicles, specifically cars.

“The main reasons for the continuous rise in registration of new vehicles are road expansion, population growth, and the increasing purchasing capacity of Nepalis,” Devi Ram Bhandari, then director of the Department of Transport Management, told Republica in 2013.

Annual car registrations increased from 7-8 percent before the road expansion to 12-14 percent. Because of the increase in motor vehicles and their speed on newly paved roads, the streets only became more unsafe for pedestrians and cyclists.

For decades, Nepal’s transportation policies have centered around building roads and highways. And always, civil engineers and regional planners who do not appear to understand urban transport have led transport plans.

In between the 1960s and 1980s, many Nepali engineers and planners studied in India, Russia, Thailand, and the US, where they picked up modernist development approaches. India, too, post-independence, adopted large-scale infrastructure and roads as the model for “national development”, which eventually trickled into the psyche of Nepali politicians, engineers, and planners.

In 1960, when then Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru used the phrase ‘cycle age’, adding that bicycles had “invaded the villages” and become “a very popular means of transport all over India,” he did so with evident regret that India was still a long way from joining advanced industrial nations in the age of electronics, jet travel, and atomic energy.

“One doesn’t have to travel to the 1960s or 70s to understand how engineering students were schooled,” said urban planner Padma Sundar Joshi, who teaches at the Institute of Engineering. “In 2010, a civil engineering student came to me for a suggestion for his school project. I advised him to do a project on cycle lanes in the Kathmandu Valley. But his fellow teachers discouraged him saying that engineers should focus on flyovers and big infrastructures, not a petty cycle lane.”

The Department of Roads, which was dominated by civil engineers and contract managers with no expertise in transport planning, was entirely focused on building motorable roads and highways. To this day, in its 70-year history, the department has not only failed to consider cycling in its plans but has proactively opposed cycle lanes proposed by other government agencies and by civil society.

In cycle-friendly cities around the world, it isn’t the central governments but the city governments that plan, fund, and build cycling infrastructures. But Nepal’s transport planning approach to this day is top-down. The federal government continues to force its development agenda on local units, often without the people’s participation. Despite federalism, city governments don’t have jurisdiction over roads or transport. The bureaucratic chief of the Department of Roads or the Kathmandu Valley Development Authority decides how the city’s roads and transport should be, not the elected mayor.

Decades of political instability have swayed the focus from the people’s everyday issues and weakened local agendas, such as cycling.

“While public discourse was diverted to managing political instability, the Kathmandu Valley destroyed itself through haphazard urbanization and motorization,” said Dixit.

Besides the top-down car-centric planning, another reason that caused rapid motorization after 1990 was because of economic liberalization and privatization policies that Nepal embraced, which was seeded in the mid-1980s with the Structural Adjustments Program. Vehicle imports were eased and dealerships were set up. Private commercial banks and financial institutions, including foreign ventures, grew more rapidly after the decade-long armed conflict. The government in turn abandoned public transport entirely to the market.

Before 1990, there were only five banks, but by 2010, there were over 308 banks and financial institutions in Nepal. All of them competed to provide easy financing schemes for private vehicles with low-interest rate loans, longer payback times, and little down payment. Many vehicle dealers also own or have equity in private banks, creating a nexus for easy financing.

As individual incomes, foreign remittance, and land value increased — hyped by the nexus between banks and the unregulated real estate market — many Nepalis could now easily afford private vehicles.

“Before 2000, it was unthinkable for a middle-class family to take a loan or sell their land to purchase a car or motorbike,” said Joshi, the urban planner. “But after 2000, as society gradually became more materialistic, taking out a loan to purchase a private vehicle became the norm among the middle class.”

The expansion of the city, which began with the construction of the Ring Road in the mid-70s and accelerated after the 90s, too encouraged private vehicle usage. Before the Ring Road, settlements were largely confined to the historic old core. As the city expanded rapidly, so did motorization.

Hope for a cycling renaissance: Reclaiming the dignity of cycling

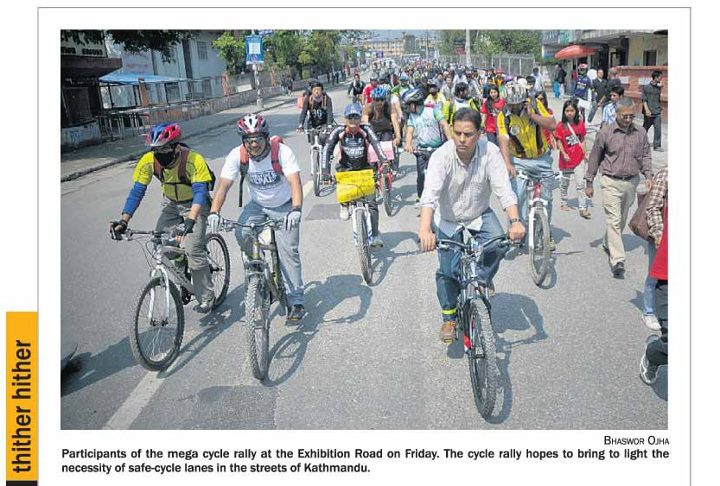

Since the last decade, with growing environmental awareness and health concerns, more and more people have adopted cycling, at least in the Valley. This interest in cycling mainly took off after the mid-2000s, as environmental concerns began to grow and organizations and activists started organizing cycle rallies.

“The decade I took over the shop saw historically low bicycle sales,” said Tirek Manandhar, who took charge of his great grandfather’s business — Pancha Narayan Asta Narayan, now called PANC Bikes — in 2000 after graduating as a mechanical engineer. “But the cycling campaigns began to attract people towards bicycles.”

But it was only after 2009, when a group of youths started the ‘Kathmandu Cycle City 2020’ campaign, that cycling started to be seen as more than just about the environment. Environmental campaigns and cycle rallies before 2009 had not called for safer cycling infrastructures and rights to the streets. In the following years, cycling campaigns began to intensify, pushing policymakers and planners for cycle-inclusive transport plans.

The death of renowned conservationist Prahlad Yonzon in October 2011 in a road accident while cycling home from his office garnered much media attention and stirred discourse about the city’s precarious cycling environment.

In April 2012, around 400 cyclists conducted a cycle rally and submitted a petition to government agencies, demanding safer cycling infrastructure. Cycle activists even gifted then prime minister Baburam Bhattarai and architect of the road expansion with a bicycle.

Responding to relentless pressure from the cycling community, in 2014, the government built a nearly three-kilometer cycle lane along the Tinkune-Maitighar road. However, the lane is not cyclable because of its faulty design.

In the last couple of years, the mayor of Lalitpur Metropolitan City has spearheaded a marked cycle lane in the city despite the opposition from the Department of Roads, which had previously blocked plans to build the Tinkune-Maitighar lane in 2000. This success owes itself to the work of a cycling advocacy organization called Nepal Cycle Society, and to all cycling activists.

Crises too have, surprisingly, encouraged the use of cycles in Nepal. Last year, with the world at standstill because of the Covid crisis, cities around the world, including Kathmandu, saw an increase in cycling. Bicycle sales skyrocketed.

“In the 11 years that I have been in this business, I have never seen such demand for bikes,” Santosh Rai, managing director of the Himalayan Single Track cycling tour company, told The Kathmandu Post.

Similarly, during the 2015 Indian blockade, many people had opted to cycle because of petroleum shortages.

“Bicycle shops were out of stock,” said Manandhar of PANC Bikes. But as the blockade ended and petroleum imports resumed, nationalist sentiments faded, and most returned to the comfort of their private vehicles.

And while there are positive signs for Kathmandu’s cycling culture, the road to achieving cycling dignity in Kathmandu remains long and hard.

“People have finally started to understand the benefits of cycling,” said Dixit, the journalist and editor. “The goal now is to convert this into a viable political agenda.”

::::::::::

[Image: A government official riding a bicycle in the 1960s. (Photo: University of Hawaii, Manoa)]

This article is Part 1 of a series on cycling in Nepal. The next part will focus on women and cycling history.

This series was produced under the Nepal Picture Library’s Kathmandu Valley Urban History Project Research Fellowship.

Prashanta Khanal Prashanta Khanal works in urban transport, air quality management, climate change, and sustainable cities.

@theprashanta