How urban design and planning failed cycling in Kathmandu

Prashanta Khanal – June 22, 2021

This article is published on www.recordnepal.com

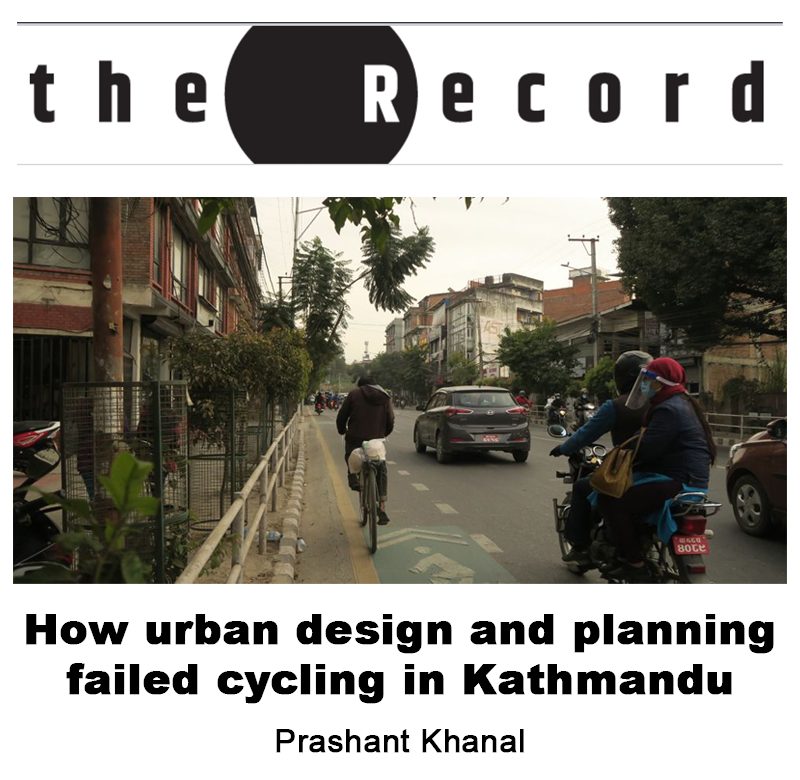

An assessment of the Tinkune-Maitighar cycling lane uncovers numerous design flaws born out of a centralized tendency to prioritize cars over public transport, pedestrians, and cyclists.

Arjun Jung Thapa, director-general of the Department of Roads, once told The Kathmandu Post that it was useless to make cycle lanes.

“The city made the cycle lane but nobody uses it,” he said, referring to the 3.1 km Tinkune-Maitighar cycle lane constructed by the Department of Roads.

Thapa is not the only government official to have made such a statement. And on a cursory look, Thapa and others like him might appear to be right. On the Tinkune-Maitighar route, cyclists appear to be using the motor road instead of the cycle lane, despite the risks of riding in mixed traffic.

But a closer look at the cycle lane and its associated infrastructure reveals a different picture. Understanding why cyclists don’t use the Tinkune-Maitighar cycle lane requires careful observation and analysis of its design. The answer that emerges is not that people don’t ‘like’ to use the cycle lane, but that the urban design has failed.

Design that failed

For cycle lanes to function properly, they need to be convenient, safe, continuous, unobstructed, connected, and direct. The Tinkune-Maitighar cycle lane does not meet the first five criteria.

First, the cycle lane is not convenient. Som Rana, a cyclist and urban planner, points out that the lane is uncomfortable to cycle on because of the type of surface material used.

In 2013, when the Department of Roads was building the cycle lane, a group of cyclists had asked that smooth asphalt or concrete be used instead of interlocking blocks as such blocks can make the surface uneven, which in turn makes cycling uncomfortable and also compromises speed. However, interlocking blocks were used regardless as the department said it had already called for a tender with those specifications. The design would be corrected in the next fiscal budget, department officials said, but that never happened.

In 2015, Clean Energy Nepal/Clean Air Network Nepal — a sustainable energy and environmental research organization that I was part of — assessed the cycle lane design — something that the department should’ve done itself — and presented the findings to two successive chiefs of the department. But more than five years later, the cycle lane remains as it is — unusable by cyclists.

“The cycle lane is physically segregated — that’s the only good thing. The lane isn’t designed from the perspective of users,” says Shristina Shrestha, a conservation architect and urban planner, who is also associated with Nepal Cycle Society.

This is largely a result of the Department of Roads’ planning practice that doesn’t hold consultations with urban planners, cyclists, and local communities. Designs and plans are made opaquely and put into place without accountability. Since cyclists were not consulted, the design did not cater to the targeted user group, and since urban planners were not consulted, there was little effort to understand how cycle lanes are designed worldwide.

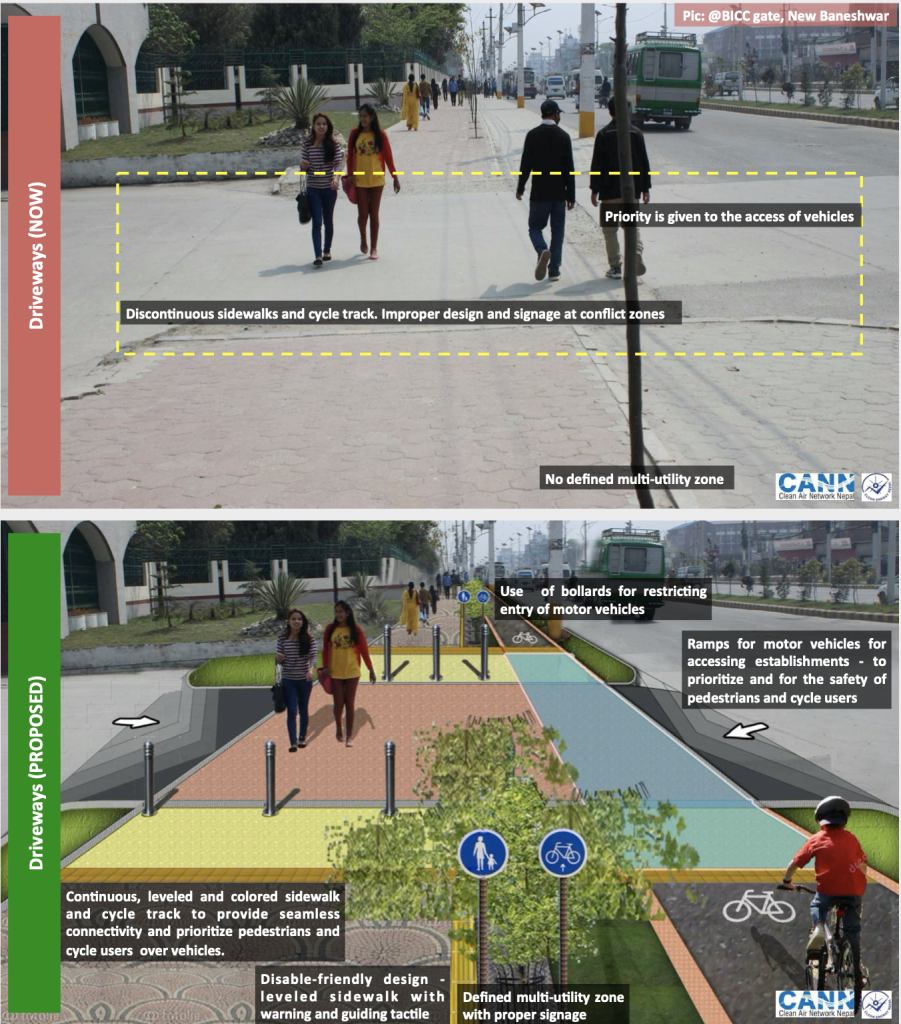

Second, the cycle lane is discontinuous and that makes it unsafe. In many places, especially where access roads are provided, both the sidewalk and cycle lane end abruptly with a sudden drop, impeding seamless mobility of cyclists. The drops almost function like a trap — cyclists have to either get down from their bicycles or learn how to bunny-hop.

The cycle lane is interrupted by numerous bridges and intersections. In a couple of sections, it is completely missing. The intersections and crossings have not been designed with cycle lanes in mind. In conflict areas, painted lanes with signage could increase visibility and prioritize movement of cyclists but none exist. Free left-turns at intersections and the absence of crossing signals place both pedestrians and cyclists at risk of being run over by motor vehicles.

Electric poles and raised manholes frequently obstruct the lane. In many sections, the cycle lane is raised from the adjacent motor road — in some instances, by as much as 0.45 meters. This not only makes cycling unsafe, but also impedes pedestrian mobility.

Bus stops are placed inappropriately in between the sidewalk and cycle lane, creating conflicts between pedestrians, cyclists, and bus users. Adjacent establishments, such as the Kathmandu District Court, have encroached on the sidewalk, turning it into motorbike parking, and forcing people to walk on the cycle lane.

Furthermore, the department recently built a pedestrian overhead bridge in New Baneshwor blocking the cycle lane.

Finally, and most importantly, a network of cycle lanes is a prerequisite to building cycling culture. Simply constructing a few kilometers of cycle lanes will not encourage people to cycle. Just as motorable traffic requires a network of roads to function, so do bicycles. Without a safe, comfortable, and direct cycle lane network in the city, it would be futile to dream about creating a cycle-friendly city.

In fact, a cycle-friendly city will require redesigning the roads throughout the city. Building wide multi-lane roads and encouraging cycling don’t go hand in hand — they contradict each other. First, the construction of highways and flyovers in the cities needs to be halted and second, any roads wider than four lanes should have two-way cycle lanes going in both directions, with a minimum width of 3 meters.

Cycling myths and excuses

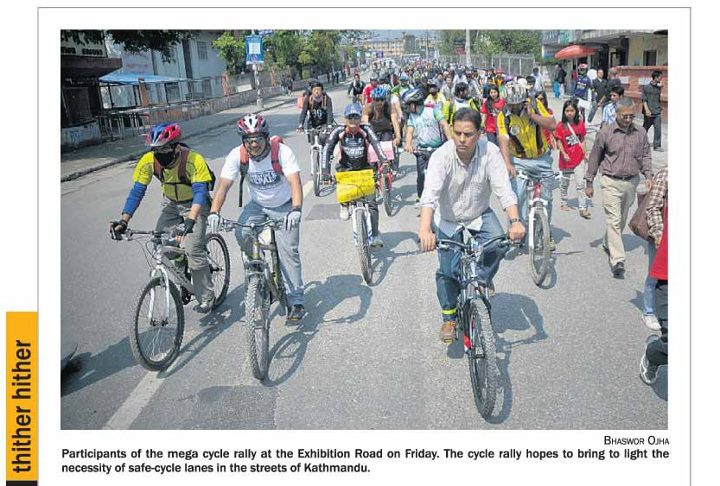

The importance and benefits of cycling — not just on mobility, but also on public health, climate change, air pollution, economy, and its role in creating equitable, livable cities — are well known. The question isn’t whether Kathmandu can become a cycle-friendly city but rather, “how do we make Kathmandu a cycle-friendly city?”

Building a cycle-friendly city doesn’t mean that every road should have separate cycle lanes, or that everyone must cycle everywhere, all the time. It simply means that those who choose to cycle have options to do so with ease and comfort. But many governmental officials, engineers, and people alike often argue that Kathmandu is not well-suited to become a cycle-friendly urban space.

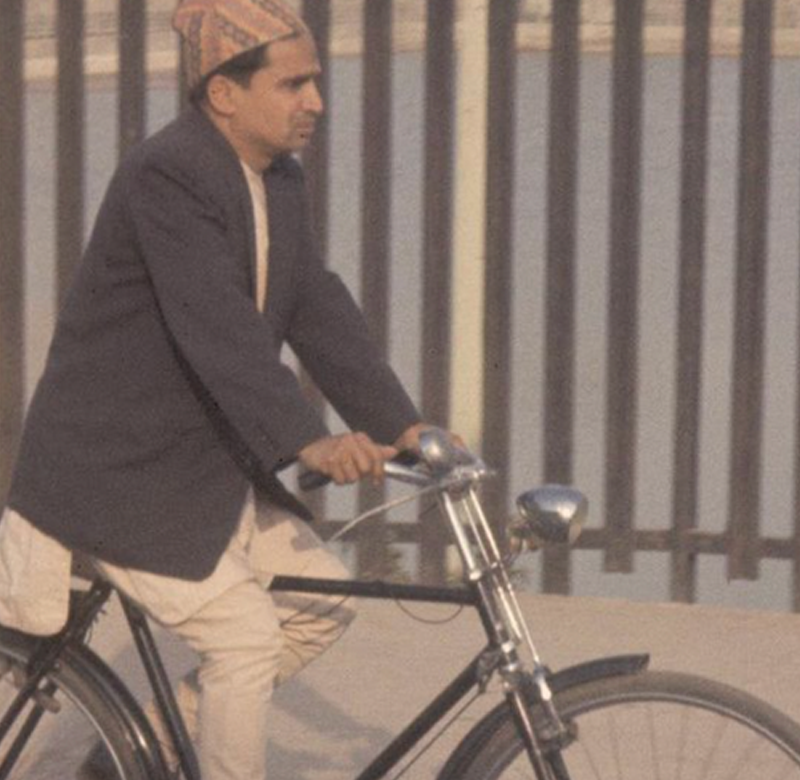

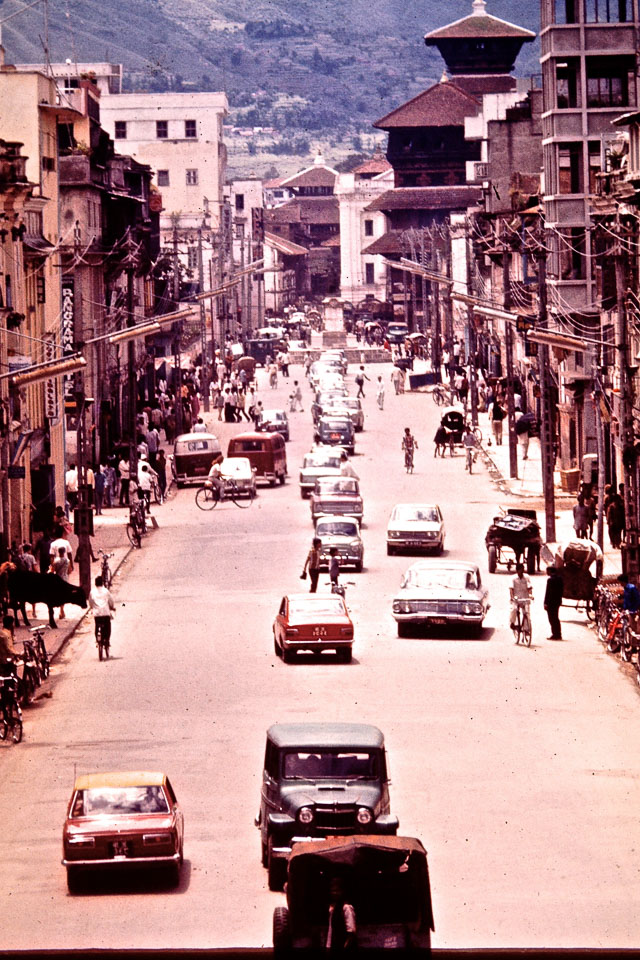

One common myth is that the Kathmandu Valley’s terrain and climate aren’t conducive to cycling. Yes, Kathmandu’s terrain isn’t completely flat, but the Valley is generally cyclable. From the 60s through the 90s, many Valley residents cycled. A 2011 study conducted by the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport and Japan International Cooperation Agency showed that the average travel distance for private vehicles in the city is about five kilometers, which is a walkable and cyclable distance. And even where the terrain isn’t too conducive for cycling, we can find ways to make road designs friendlier for cycling, such as reducing the road gradient and building connecting bridges. With electric-assist and geared bicycles, cyclists are easily able to cover large distances and uphill terrain.

Besides some inconvenience during the monsoon, the Valley’s climate is comfortable for cycling — it is not too harsh in the winter or too hot in the summer. Plenty of people cycling in the Tarai during the summers and the monsoon, and in Copenhagen during the snowy winters, suggest that climate isn’t a key factor. Some urban design interventions, such as creating tree shades and rain shelters, could further add convenience for cyclists.

Another excuse is that Kathmandu’s roads are already congested and aren’t wide enough to build cycle lanes. This begs the question: who do we prioritize first when it comes to road space. The priority has never been pedestrians or cyclists; it has always been motorized vehicles. Urban mobility is not so much about space as it is about priority. Globally, the accepted norm in urban planning is to prioritize pedestrians first, followed by cyclists and public transport, and private cars last. But Nepal’s cities plan in reverse — the car is at the center of transport planning. Unless we change our priority, and stop worrying about cars stuck in traffic over the safety and convenience of pedestrians, cyclists, and public transport users, inequitable access to mobility and congestion will continue.

Space for cycle lanes on existing roads can be created by reducing their lane width. Urban roads designed as highways with 3.5 to 3.75 meter lanes can easily be reduced to 2.5 meters. This will also make roads safer for all road users, including private vehicles. On smaller roads, traffic calming measures can help make spaces safer for cyclists.

Oftentimes, while sharing cycling success stories from European cities, a common response is that “we are not Copenhagen”; they are relatively wealthier, developed cities whereas we are not. But in fact, the Copenhagen of today wasn’t the same Copenhagen a few decades back. They too had car-centric transport planning, but in the 1970s, they made a turnaround, realizing the repercussions of car-centric transport planning, and became one of most cycle-friendly cities in the world. Funnily enough, the same response is never forthcoming while planning urban highways and flyovers in a city where the majority of residents can’t afford cars, unlike in European cities. Developing cities need to invest more in low-cost cycling infrastructure rather than expensive road infrastructure that rich cities can afford and we can’t.

READ MORE: Cycling lessons from Copenhagen

Yet another argument that department officials often make for not building cycle lanes is that there just aren’t enough cyclists on the road. That is just not true — cyclists are just invisible to those who don’t want to see them. The approach needs to be one of ‘if you build it, they will come’. We cannot wait for cyclist numbers to increase before building a cycle lane. Not surprisingly, the same institution that wants to see cyclists on the streets before building cycle lanes has failed to build cycle lanes in the Tarai, where a great number of people cycle.

There is even legislation to help planners and officials prioritize cycling. The National Transport Policy, formulated in 2001, clearly says that “in urban roads, cycle lanes shall be managed separately”, as does the National Road Standards. Among some other policies and plans, the Environment-friendly Vehicle and Transport Policy (2014) also includes provisions for cycling.

For Department of Roads officials and many politicians, cycling symbolizes regression. To them, cycling connotes backwardness and a lack of progress while wide roads and many cars symbolize prosperity and development.

More power to city governments

For decades, the Department of Roads has ignored the rights and needs of cyclists. It’s unfortunate that the department’s engineers do not acknowledge the need for cycling infrastructure as their priority appears to be to move vehicles swiftly at any cost, be it at the expense of people’s lives.

The department’s road designs have killed thousands of people every year in accidents and injured many more. Data from the Metropolitan Traffic Police Division shows, in the Kathmandu Valley alone, road crashes kill over a hundred people annually. Pedestrians and cyclists are the most vulnerable, followed by motorbike riders. In the entire country, in 2019, road crashes killed 2,736 people and seriously injured 10,731.

The Department of Roads has a very large budget, and almost all of it goes towards building and maintaining roads and highways. During the pandemic, the department had the opportunity to redesign the city’s roads and allocate more space for walking and cycling, as has been done in the many cities around the world. But not surprisingly, there have been no such plans. Instead, all they did was blacktop the same roads they had blacktopped a year or so ago.

In cities around the world, it’s not the federal government but the city government that invests in and builds cycling infrastructure. In Nepal, the city governments do not have jurisdiction over roads that are wider than eight meters. The Department of Roads is a federal entity that answers to the federal Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport. Roads within municipalities need to be designated urban roads so as to come under the jurisdiction of the city governments. The department’s budget needs to also be redirected to local governments. With larger budgets for their roads, municipalities could then allocate more funds to sustainable mobility.

“Despite the political change, from Panchayat to Loktantra, the top-down planning culture hasn’t changed,” says urban planner Kirti Joshi. “Local governments are not given enough power. City governments have to take permission from the Department of Roads for any interventions.”

The political decision of how to build the city and who to prioritize should be in the hands of the elected mayor, not some bureaucratic officials who aren’t accountable to the public. The Department of Roads should simply be an implementing partner or a technical agency; it shouldn’t be able to tell cities how to design their spaces.

“The lack of clear jurisdiction over the roads, clarity on road nature/hierarchy, and institutional awareness create barriers in swift planning for a cycle city,” says Shrestha. “Political will is the most important element in making changes and the Lalitpur mayor has displayed that.”

The construction of cycle lanes in Lalitpur shows the importance of local government. Despite resistance from the Department of Roads, Lalitpur Metropolitan City forced its way to build several kilometers of cycle lanes that are being further expanded. The city government was able to do this because it listened and consulted its people, many of whom are cyclists.

Though Lalitpur’s marked cycle lane — instead of one that is physically segregated — is not the preferred design as it is not entirely safe, it has gained widespread attention and displayed inclusivity, giving a sense of respect and ownership over the city to marginalized cyclists, who tell me that they now feel that the road belongs to them too.

Lalitpur’s marked cycle lanes are only 1.2 meters wide. Safer cycle lanes require physically segregated lanes with a minimum width of 1.8 meters (for one way). This minimum width allows two bicycles or wheelchairs to pass each other comfortably. A cycle lane is safe enough only when a child can cycle with ease and safety, all on their own.

“According to our observation, 30-40 percent of the marked cycle lanes in Lalitpur can be converted to dedicated cycle lanes,” says Rana, who is also associated with Nepal Cycle Society and is helping Lalitpur Metropolitan City design its cycle lanes. “But the Department of Roads hasn’t given us permission to install bollards to segregate cycle lanes from the motor road.”

Making cities cycle-friendly is not merely a technical or financial issue, but a political one. The politics of whose interest to prioritize, of who owns urban spaces and roads. Do we design our mobility for the benefit of a few that can afford cars or for everyone else? Do we continue to spend money on roads that will further entrench inequality in the city, or invest in public transport, and pedestrian and cycling-friendly infrastructure?

::::::::::

Cover photo: A cyclist riding his bicycle on the marked cycle lane in Lalitpur. Without physical segregation, the cycle lane is very safe for cycling but at least, it provides a sense of acknowledgment and respect for cyclists. (Photo: Prashanta Khanal)

The article is Part 3 of a series on cycling in Nepal. For Part 1, A history of cycling in the Kathmandu Valley, click here. For Part 2, a history of women and cycling in Nepal, click here.